Feelings come and go–they can change from moment to moment with what we’re experiencing. A feeling can be triggered by a thought, a behavior, or an interaction with the environment or another person. I often find myself in conversations with people about how others influence or impact their emotions. Sometimes interactions with others are pleasant, and increase our happiness and overall satisfaction. Other times, social situations can make us feel bothered, offended, irritated, angered, frustrated, annoyed, and/or a host of other things. Even at times when we might be completely content or happy, another person can enter our experience with a different feeling or energy that can completely and immediately shift our mood. And often, when our mood shifts, we approach the rest of our day differently. We can go from being positive and productive to becoming grumpy and withdrawn, because of what another person said, did, or felt.

A lot of times these interactions are unavoidable since we can’t control the types of emotional stimuli emitted from others, and in our day to day lives, most of us are always receiving some type of external stimuli. What is in our control is the way we respond to what we’re given. We can decide if the feeling we’ve received from somewhere/someone else will remain or dominate, or if we’d like to return to our original or another feeling state.

We all know someone who spends a lot of time complaining or venting about what they don’t like or how things are going wrong, and at times, we may be that person. As individuals, we each perceive many different things as wrong or not likeable. We all feel angry, sad, disappointed, or frustrated at times, so it’s likely that we’ve held both of these positions, the complainer and the listener, at some point or another. Sharing our feelings with others is an important part of relating. We feel connected, validated, and understood, when sharing something that can be held, mirrored, or reflected by another. This is a good thing.

However, it gets complicated sometimes. Other people’s emotions aren’t always welcomed or wanted. They can sometimes feel intrusive or burdensome, leaving us with a feeling that interrupts our previous level of functioning or being, or with a feeling that we simply just don’t want. Everybody knows the old saying, “misery loves company.” And though it doesn’t necessarily mean that people are going around intentionally trying to make you miserable because they’re miserable, it doesn’t change that frequently, that is the outcome. As said before, it feels good to be listened to, understood, and connected with. When our pain, sufferings, and idiosyncratic irritations are heard, it makes our perceptions valid and real.

But what do you do when your coworker comes and complains to you about how much they hate your boss, listing every wrong the boss has ever done towards them, engendering angry and resentful feelings in you towards the boss too? What about when your significant other comes home in a bad mood, and lets the bad mood influence how they relate to you? Or when that reckless driver cuts you off on your morning commute? There’s no question that most of us would have some type of negative emotion or reaction to any of these scenarios. These are all examples of uninvited emotional experiences unexpectedly entering your space, which is usually not cool and makes people angry. I’ve heard people describe events like this as ruining their entire day. Not all of us will have our whole day ruined by one of these unfortunate, unavoidable situations, but plenty of us would give considerable time and energy to feeling bad, sad, or mad. And that’s fine. We should all have space to feel our feelings and move through or process them as we choose. But I think we should also give ourselves options. We have some ability to choose how we feel. How about asking yourself, “how do I want to feel?”

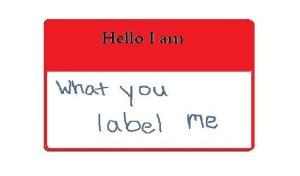

Also, “Is this emotion useful or necessary?” and “How do I actually feel?” Not everyone is well versed in identifying and naming feelings. Sometimes we react before taking the time to really think and determine for ourselves what we feel. Looking inside to assess your own emotions is an important step, since lots of what we feel and experience comes from outside of us. Sometimes our emotions aren’t even really ours. Through transfers of energy, projective identification, displacement, and other energetic or psychological processes, certain feelings can be put into us by others. Do you want to hold onto a negative emotion that was transferred to you by someone else? If the feeling can be used, then maybe it’s worth keeping, but if not, why hold on to it?

Of course this is much easier said than done. Deciding to change your mood, and actually doing it can be extremely difficult. Yet, rewarding. It takes effort and focus to get back to a space of contentment when you’ve been thrown from it, but the effort can be worthwhile. Most of us don’t want to feel bad and usually we’re overall better people when we’re feeling good. We’re more productive, engaged, polite, social, and present in our lives when we’re in a good mood. So, how do you want to feel?

Here’s a short list of tools I’ve found helpful when making the choice to feel good:

1. Immediate intentionality. As soon as you notice an unpleasant or unwanted emotion interfering, make time or find space to reflect, meditate, pray, connect, or any practice that can center your thoughts on the feeling what you want. Be intentional and stay focused on what you want.

2. Change your behavior. Sometimes thoughts/feelings influence our actions/behaviors, but our actions and behaviors can also influence our thoughts and feelings. Start with your behavior and see if your emotions follow (i.e. smile, listen to music, exercise, do anything you enjoy)

3. Focus on gratitude. Studies show that thinking of things that you’re happy about and thankful for leads to good health and increased joy.

Feel free to share any tips or tools you use to stay in your mood of choice!